Nulla Lux Nulla Nox

1. The Beginning

In 2023, I took part in the Florence Biennale for the first time.

I presented six small-format pieces as an experimental fiber project, where I sought to turn thread into a living experience, playing with mirror neurons, nonverbal language, and emotional resonance.

It was my first time outside my country, and the fact that it happened in Florence didn’t feel like a coincidence.

Seeing so many artists bring their very best, immersing myself in their work, and forming friendships that continue to this day made me realize that my first Biennale was meant to be a lesson.

Exploring Florence —its streets, museums, and galleries— filled me with inspiration that I carried back to my studio. My goal was clear: to return and show everything I had learned, everything that city and its culture had given me.

By the end of January 2025, we decided as a family that the entire year would be devoted to creating a large-scale piece, one that would embody all I had absorbed in that remarkable city.

When I learned about the Biennale’s theme, the first image that came to mind was Cabanel’s Fallen Angel. But I didn’t want to recreate it; I wanted to make my own version, something deeply personal that I needed to express.

Drawing from my experience in Florence, from Michelangelo’s anatomical precision (as a kinesiologist, anatomy is one of my greatest passions), from Artemisia Gentileschi, and other masters who resonate with my sensibilities, I began sketching what would become my greatest challenge: my first non-experimental work, a piece where I poured all the experience gathered from four years of pictorial crochet.

2. Conceptual Meaning of the Work

Although the Biennale’s theme was light and darkness, my rebellious soul kept telling me to go beyond those two great poles. I knew there was something in between —a point suspended between one and the other— that resonated deeply within me.

That’s where the name of my work comes from: Nulla Lux Nulla Nox (neither light nor darkness, in Latin).

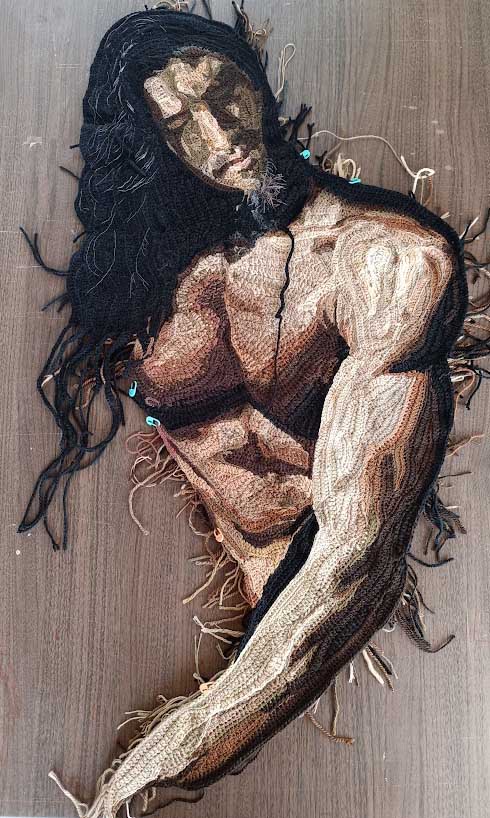

I took my “muse,” the fallen angel, as a reference, but I didn’t want to portray him at the moment of defeat. I wanted to show him later, in the time after the fall.

I needed to reveal the humanity that emerges after a decision has been made. That’s why his body is more anatomically detailed: his skin darkened and weathered by time, his long black hair streaked with gray, and his posture suspended in a question — do I rise, or do I remain here?

What I wanted to express is that eternal present that every human being has experienced — that moment when the darkness has passed, but dawn has not yet arrived.

That place of uncertainty where the surroundings no longer matter, and it is only you and the free will to decide what comes next.

And then you realize that, regardless of the external circumstances —the light and the darkness that we cannot control— there exists an in-between space that belongs solely to us: the moment of decision.

3. The Technical Dimension – The Body and the Living Fiber

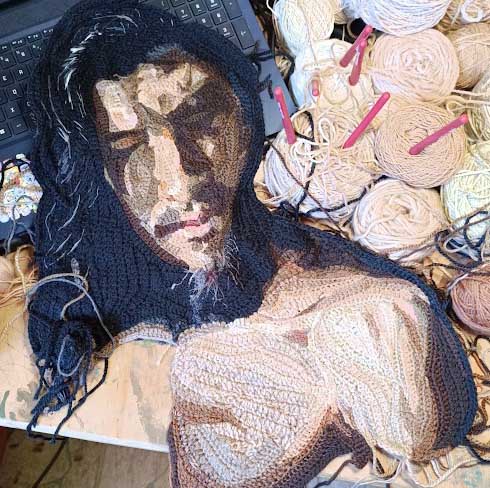

This work is born literally out of nothing. It begins with a single point — in this case, from the center of the nose — because I always start where I want the viewer’s gaze to rest. From there, the piece grows outward, expanding like an organic form.

Unlike painting, I don’t work on a fixed surface such as a canvas. The piece grows as far as I decide it should, supported by a table adjusted to the needed dimensions.

In this technique, there are no layers, no blending of tones: everything depends on finding the exact thread or adapting myself to the tone available. It is an uncertain process, because the work evolves as it grows, and I often feel that I’m not fully in control of what will emerge — I depend entirely on the colors and tones the market provides.

The weaving must always progress continuously; I can’t work on one side and then the other, as that would break its coherence.

That’s why I began with the head, then moved to the hair, shoulders, arms, chest, and continued down through the anatomy to the very last toe.

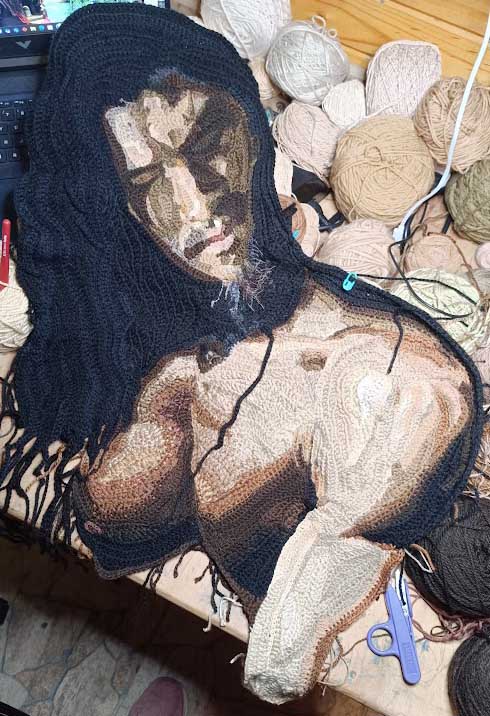

Following the concept of the work, I needed this body to feel as if it were in motion — to appear alive.

I chose an intermediate, ambiguous posture, one that offers the viewer the privilege of completing the meaning of the scene through their own experience:

Is it a body rising, or one that remains in defeat?

I wanted the pose to be complex, with a dissociation between the shoulder girdle and the pelvic girdle, creating a composition of diagonals: one arm bearing weight, the other relaxed; one leg extended, the other bent.

My challenge was to let this duality be expressed even through the body’s extremities.

Once the body was finished, I noticed it leaned slightly to one side. To balance it, I decided to work on the wings, following the same logic of opposites: one open and magnificent, the other closed, built upon a black base with light and luminous accents.

It was a new challenge — no longer anatomy, but something entirely different, outside my domain.

I began observing the wings of my hens, holding them, studying their structure, trying to understand how they were made. That’s when I discovered the only way to achieve a powerful effect was to create feather by feather.

It was an adventure outside my comfort zone, but I enjoyed it deeply — especially when, stepping back, I saw the piece from afar and realized those wings had texture, volume, and a real sense of strength.

The next challenge was the fabric, another element beyond my usual anatomical focus. I needed it to move, to breathe.

For that, I turned to embroidery, a technique I rarely use, but which in this case allowed me to add light, folds, and reflections. At first, I thought I wasn’t achieving the effect I wanted — until I took a photo from a distance and realized I had captured exactly what I sought: movement, creases, brightness, and realism.

Finally, the sky brought its own challenge. I wanted harmony and emotion through the use of different tones, creating a sense of movement that would evoke the passing of time, visible in the waves of dark and light red hues.

In contrast, the ground remains flat and still, representing that eternal present in which the figure stands.

The sky moves, but the ground does not — a tension between the flow of time and the frozen instant.

1. L’inizio

Nel 2023 ho partecipato per la prima volta alla Biennale di Firenze.

Ho presentato sei opere di piccolo formato come un lavoro di fibre sperimentale, cercando di trasformare il filo in un’esperienza viva, giocando con i neuroni specchio, il linguaggio non verbale e le emozioni.

Era la mia prima volta fuori dal mio Paese, e il fatto che fosse proprio Firenze non credo sia stata una coincidenza.

Vedere tanti artisti portare il meglio di sé, lasciarmi attraversare dalle loro opere e creare amicizie che durano ancora oggi mi ha fatto capire che quella prima Biennale era una fase di apprendimento.

Ho percorso Firenze: le sue strade, i musei, le gallerie. Tutto ciò è diventato materiale prezioso che ho portato nel mio atelier, con un obiettivo chiaro: tornare e mostrare tutto ciò che avevo imparato, tutto ciò che quella città e la sua cultura mi avevano donato.

Alla fine di gennaio 2025, abbiamo deciso come famiglia di dedicare l’intero anno alla realizzazione di un’opera di grande formato, che racchiudesse tutto ciò che avevo assimilato in quella città straordinaria.

Quando ho saputo il tema della Biennale, il primo pensiero è andato a L’angelo caduto di Cabanel. Non volevo farne una copia, ma creare una mia versione, qualcosa che sentivo il bisogno di esprimere.

Ispirata da ciò che avevo vissuto a Firenze, dallo studio anatomico di Michelangelo (sono chinesiologa e l’anatomia è una delle cose che amo di più), da Artemisia Gentileschi e da altri maestri affini alla mia sensibilità, ho iniziato a disegnare quello che sarebbe diventato la mia più grande sfida: la mia prima opera non sperimentale, un lavoro in cui ho riversato tutta l’esperienza maturata in quattro anni di crochet pittorico.

2. Concettualità dell’opera

Anche se il tema della Biennale era la luce e l’oscurità, la mia anima ribelle mi diceva che volevo andare oltre questi due grandi poli. Sapevo che esisteva qualcosa nel mezzo, un punto sospeso tra l’uno e l’altro che risuonava profondamente dentro di me.

Da lì nasce il nome della mia opera: Nulla Lux Nulla Nox (né luce né oscurità, in latino).

Ho preso come riferimento la mia “musa”, l’angelo caduto, ma non volevo rappresentarlo nel momento della sconfitta. Volevo mostrarlo più tardi, nel tempo dopo la caduta.

Avevo bisogno di esprimere l’umanità che emerge dopo una decisione. Per questo il corpo è reso con maggiore attenzione anatomica: la pelle scurita e segnata dal tempo, i capelli lunghi e neri con fili d’argento, e una postura che racchiude una domanda: mi rialzo o resto qui?

Quello che volevo raccontare è quell’eterno presente che ogni essere umano ha vissuto almeno una volta, quel momento in cui l’oscurità è passata ma l’alba non è ancora arrivata.

Un luogo di incertezza dove l’ambiente esterno smette di avere importanza, e restiamo solo noi con il libero arbitrio di decidere cosa viene dopo.

E allora ci si accorge che, al di là delle circostanze esterne, la luce e l’oscurità che non possiamo controllare, esiste uno spazio intermedio che appartiene solo a noi: il momento della decisione.

3. La dimensione tecnica – Il corpo e la fibra viva

La mia formazione come chinesiologa mi ha dato una mappa precisa del corpo umano, una mappa che in seguito ho trasformato in crochet pittorico.

Studio la muscolatura nei dettagli, osservo come la tensione, il movimento e il ritmo modellano il corpo. Attraverso il filo ricreo quello stesso movimento vitale.

Ogni filo diventa una fascia, una pelle, un muscolo.

Il crochet smette di essere artigianato e diventa anatomico, vivente.

Non è più un corpo rappresentato, è un corpo tessuto.